Best Practices for Beekeepers

Beekeeping is an art and a science which has been practiced for thousands of years. While beekeeping practices have changed through the years, beneficial management decisions, including attention to nutrition and health, continue to be important considerations.

-

Honey bees (Apis mellifera) are the most commonly managed bee in Pennsylvania, and around the world, and is the primary focus of this chapter. However, several other bee species are managed for pollination services, including bumble bees and mason (or orchard) bees in Pennsylvania. These species are native in Pennsylvania and in landscapes with sufficient nesting habitat and forage, can be quite abundant (see also the “Best Practices for Forage and Habitat” section). Thus, in Pennsylvania, growers can often use the pollination services of these wild bee populations and do not need to acquire managed bees. However, there is increasing interest in managing these bees for specific crops, including greenhouses and orchards. More information is provided at the end of this chapter on these alternative pollinators.

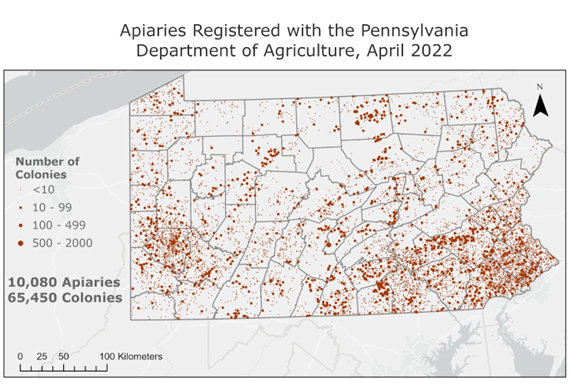

In Pennsylvania, beekeepers who manage 10 or fewer honey bee colonies make up about 82% of the 6,500 registered beekeepers in PA. Many of these hives are permanently located and managed on the beekeeper’s property. Some of these hobbyist or backyard beekeepers are very experienced, while others are beginners.

In addition to honey bee colony management decisions, all beekeepers should be aware of laws and regulations concerning beekeeping. Whether a beekeeper is engaging in a hobby or a gainful enterprise, there are laws and regulations which have been enacted to protect against negligence which would adversely affect other people or property. It is a beekeeper’s responsibility to provide the best environment for their honey bees while being a good neighbor.

This Chapter provides general recommendations and expectations for honey bee colony management in different landscapes, as well as guidance for engaging with different audiences, from the public to professional pesticide applicators. Further information on managing bumble bees and orchard bees is provided in the last sections.

-

Beekeepers are urged to attend beginning beekeeper classes, conferences, and workshops. In addition, beekeepers may wish to join the Pennsylvania State Beekeepers Association, as well as one or more of the over 35 local beekeeping organizations in Pennsylvania. These organizations provide helpful information- including critical information on local conditions - through their meetings and newsletters.

New beekeepers should seek reliable instruction before keeping honey bees. When seeking beekeeping instruction and education, exercise caution with social media content, as it is not always reliable. It is important to understand basic bee biology and behavior. All beekeepers need to be aware of what a healthy colony looks like at different times of the year. A beginner class will also help the new beekeeper understand bees and plan their management. Instruction includes methods of acquiring bees, recognizing and treating diseases and pests and risk management. Resources on advanced management techniques such as queen biology, queen cell production, cell builders, and many more can be found at the Center for Pollinator Research and Penn State Extension websites.

A beekeeping guide and an award winning Beekeeping 101 course are available online from Penn State. More advanced online courses will be available soon. Penn State Extension regularly offers additional virtual courses and webinars, including the “Beekeeping around the World” series and “Beekeeping Basics in Spanish”. Additional information, including Spanish language articles, can be found on the Center for Pollinator Research’s “Resource Library”.

The PA Apiary Advisory Board has created the Voluntary Code of Conduct. These Best Management Practices (BMPs) provide information for maintaining honey bee colonies in Pennsylvania and contain proven guidelines for keeping bees in any landscape, from urban to rural.

Following these BMPs can help to minimize nuisance situations and provide useful and practical guidelines for beekeepers, as well as municipalities considering zoning or ordinances changes. A model ordinance is available.

If you are interested in selling your honey, please follow the guidelines of the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Food Safety, outlined in the following documents on selling honey, processing honey, and information on the Food Safety Modernization Act’s guidelines for preventative controls for human foods.

-

The Pennsylvania Bee Law, passed in 1994, was a collaborative effort between the Pennsylvania State Beekeepers Association and the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Plant Industry.

According to the Bee Law, anyone who manages honey bees in PA is required to register their bees with the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture.

Instructions detailing how to register or review your personal beekeeper account on PA Plants are available. Alternatively, you may still use the Mail-In Apiary Registration form. The Apiary License is valid for up to two years and costs $10. Registered beekeepers may access their apiary accounts, and the information associated with them, by logging on to PA Plants.

The PA Department of Agriculture (PDA) enforces the Bee Law through the State Apiarist and Apiary Inspectors. There are usually six Apiary Inspectors working in various PA counties from mid-April through most of October and the State Apiarist works year-round out of the Harrisburg office.

Apiary registration has a number of benefits:

- Increasing the efficiency of the apiary inspection service. Apiary inspection is an early detection safeguard for the beekeeping industry. If necessary, methods such as quarantines and best management practices may be used to slow the spread of pests, diseases, and pathogens.

- Many public health pesticide applicators will attempt to contact beekeepers if they plan to spray within a certain distance of registered bee yards. By maintaining accurate bee yard locations and contact information on PA Plants, it is easier for pesticide applicators to notify the beekeeper. The beekeeper can then decide whether to move or cover hives. Please note that the pesticide applicators are not required to do this. Sometimes, due to an immediate public health risk or weather concern, the pesticide application must be done immediately and the beekeeper is not notified. Additional information on beekeeper notification of pesticide applications can be found in the “Best Practices for Pesticide Use'' section of this pollinator protection plan.

If a beekeeper wishes to sell queen bees or nucleus colonies to other PA beekeepers, they will be inspected twice a year. If no disease is found, a Queen and Nucleus Producer Permit will be issued. This permit is valid for one year.

The Bee Law also monitors the movement of honey bees, queens, and used equipment entering or exiting Pennsylvania in order to mitigate bee disease outbreaks. Bees and used equipment are inspected within 30 days of the proposed shipment date. A permit is issued if no disease is found.

-

The plants or floral resources available to honey bees and other pollinators are crucial to their success. Flowering plants within a one-half to one mile radius of an apiary are the most critical to the health of the bees, although bees will forage up to 3 miles from their apiary if forage is scarce. Access to a diversity of flowering plant species is extremely important to the health of the bees. Keep in mind that bees forage throughout the year - from early spring through late fall. Bees also need access to consistently available water.

Beekeepers can use Google Maps/Earth and explore within a one to two-mile radius of the intended apiary. Beekeepers should select locations that have an abundance of diverse vegetation, since these are more likely to provide year-round forage. Key landscape plants include flowering trees, shrubs, and clover. In addition, remember that many plants bloom only for a few weeks, and thus having a diversity of plants will help ensure longer access to forage.

Penn State University’s Center for Pollinator Research provides a free web-based tool, Beescape, for assessing the suitability of an area for honey bees and other pollinators. This tool is similar to Google Maps, in that it provides satellite or street views from across the continental United States. Users can select a region of interest, and obtain information on the land use patterns, seasonal foraging quality, wild bee nesting habitat quality, and pesticide risk. Additionally, Beescape provides an estimate of the economic value provided by bee pollination of agricultural crops in the selected area. Finally, Beescape provides information on the monthly temperature and precipitation patterns in the selected area, for the current year, past year, and 10 year average.

If the hives are located on the beekeeper's property, he or she may wish to plant pollinator friendly plants to add to the bees’ diet diversity. More information and methods to improve the forage quality of a landscape can be found in the “Best Practices for Forage and Habitat” section of this pollinator guide. If you are interested in learning about which plants your bees are foraging on, you can send honey and pollen samples to the Penn State Honey and Pollen Diagnostics Laboratory for analysis.

Water should always be accessible to colonies. If there is no natural source close by, utilize artificial water sources such as bird baths, trickle hoses or in-hive feeders if natural water is not available. Remember to keep these sources full of water from early spring until late fall.

The beekeeper should consider supplemental feeding if nectar and pollen resources are not available. If bees do not do well in a location after two years, consider relocating to a more appropriate location with more plant diversity. It is important to note that honey bees can not be kept in state or national parks or forests, on state game land, or other areas that are restricted by the state or local municipalities.

In Pennsylvania, bears are common and can readily destroy beehives. Instructions for constructing an electrified bear fence is available in this guide, an alternative panel fence design can be found here.

-

Honey bee colony management varies through the seasons, which is described in detail in this Penn State Extension article. In late winter and early spring honey bee queens resume egg-laying and the colony initiates brood rearing. As outdoor temperatures rise and spring flowers bloom, bees will begin foraging for nectar and pollen. Beekeepers must monitor their colonies regularly at this time of year to make sure they have adequate resources to feed their young and keep the colony warm. Establishing new colonies is most often done in the spring. By late spring, floral resources have been available for several weeks and remain plentiful. The colony has been actively rearing new bees during this time. The increased population in the colony triggers the rearing of drones (males). Beekeepers must check their colonies regularly in spring to make sure the brood chamber and honey supers are not full, and that swarming has not been initiated. During the summer, the colony collects and stores the honey that the bees will consume in the fall and winter months. If the colony swarmed or the beekeeper made a split, the newly emerged queens will have mated and begun laying eggs. This is the season that many beekeepers harvest honey and a key time to start monitoring for Varroa mites and conducting treatments. Summer nectar flows diminish in July, resulting in a nectar dearth or scarcity. Late in the summer (August and September) colonies also begin to rear winter bees, which are essential to colony winter survival. At the beginning of fall in many regions, there is another nectar flow that beekeepers call the fall flow.

Continued monitoring for Varroa mites is necessary at this time; the mite population should be as small as possible for the best possible outcome of overwintering. Honey bee colonies will soon be completely reliant on their honey stores, so beekeepers pay special attention to the weight of their colonies in the fall. Winter begins as the last flowers are eliminated by freezing temperatures, the summer bees have died off, and brood-rearing comes to an end. For a more detailed look at beekeeping through the seasons, see here.

Pennsylvania’s geography is highly diverse. Differences in geography and plant communities are evident with changing latitude, longitude, and altitude. Because of this, seasonal conditions vary across the state. Indeed, the same flowers may bloom at different times across the Commonwealth, creating local honey flows. A honey flow occurs when at least one of the bees’ major nectar sources is in bloom and the weather is favorable for nectar collection. Established colonies throughout Pennsylvania can produce surplus honey in May and June. However, the central, south, and eastern counties often experience fewer summer rains, resulting in fewer inches of water, which can reduce or eliminate a fall honey flow. Micro-climates around mountainous areas, forests, and lakes, as well as housing developments and large agricultural tracts, can have a varying impact on honey flows. Local beekeeping organizations have detailed information concerning conditions nearby and are excellent resources for new beekeepers. Additional information about local landscape and weather conditions can be found on Beescape. If you are interested in learning about which plants your bees are foraging on, you can send honey and pollen samples to the Penn State Honey and Pollen Diagnostics Laboratory for analysis

Supplemental feeding is a must in times of limited forage and drought. Sugar syrup, candy blocks and pollen substitutes may be used and are essential management requirements

Keeping records of inspections, treatments, supplemental feedings, queen problems, and other management tasks is helpful to all beekeepers. Some beekeepers use a notebook or spreadsheets while others prefer to do this electronically through a program like Hive Tracks.

In April and May of each year, Penn State offers the Annual Beekeeping Management and Winter Loss Survey. This survey was originally conducted by Ken Hoover, and data is available for more than 10 years. Data from this survey has been used in multiple research studies, and demonstrated the importance of Varroa mite management, landscape quality and weather in reducing winter losses. Continuous data collection will allow the Penn State Center for Pollinator Research to create a decision support tool to help beekeepers take steps to improve colony survival in the future. Please consider contributing to this survey.

-

A number of parasites, pests, predators and diseases, and other maladies and viruses can be harmful to honey bees. It is the beekeeper’s responsibility to monitor, identify and remedy these situations. Beekeepers should routinely open and inspect hives to monitor for the presence of pests and diseases. It is critical for beekeepers to learn to identify normal honey bee development and to be able to identify the queen, workers, drones, and stages of larval growth. This will ensure beekeepers can detect problems early and take necessary steps to deal with any issues. Penn State’s Beekeeping Basics Manual is an excellent resource for general beekeeping information. In addition, The Bee MD is an interactive diagnostic tool for helping beekeepers understand problems they may be having. The Honey Bee Health Coalition offers resources and education for beekeepers, land owners, and growers to improve the health of honey bees.

Many common pests and diseases of honey bee colonies, such as wax moths, small hive beetles, ants, chalkbrood, American Foulbrood, European foulbrood, and viruses will not thrive in a strong colony and are usually symptoms of a weak, small or otherwise stressed colony. Colonies may be stressed by poor weather conditions, poor forage, or heavy Varroa mite infestations. Even infections with Nosema - now called Vairimorpha, a gut microsporia, can often be cleared by a healthy colony (additional information about Nosema infections).

It is strongly recommended that beekeepers use an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach to manage pests and diseases.

IPM is the use of several different pest/disease control techniques in combination or in rotation throughout the year. IPM utilizes cultural, mechanical, and chemical controls. Cultural controls are those that limit the reproduction of the pest. In beekeeping that includes the use of pest-resistant stock or a brood break. Mechanical controls are those that aim to increase mortality of a pest. In beekeeping that includes drone brood removal (mite trapping) and screened bottom boards. Chemical controls include the application of chemicals to quickly reduce a pest’s population by introducing a chemical agent to the hive. Overall, IPM relies on knowledge of pests and regular monitoring of pest populations to determine when interventions are needed based on an economic threshold. In addition, a rotation of controls, rather than reliance on just one method, diminishes the chances that a pest population will develop resistance. See The Importance of IPM for Beekeeping and Methods to Control Varroa Mites: An IPM Approach for more details.

Studies from Penn State have demonstrated that organic beekeeping is just as effective as traditional beekeeper practices for supporting healthy and productive bees. For more information, see the following guide: An Organic Management System for Bees.

Beekeepers should also visit the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Apiary and Pollinator Services website for additional information, identification, and controls for diseases and pests.

Invasive pests such as the Spotted Lantern Fly impact beekeeping and require beekeepers to follow state guidance on inspection of equipment and vehicles when transporting colonies outside of a quarantine zone.

-

Pesticides can have a number of negative effects on honey bees, which are discussed in detail in the “Best Practices for Pesticide Use” section of this plan. Thus, beekeepers, homeowners, pesticide applicators, and land managers need to take precautions to reduce pesticide exposure. In this section, the focus is on steps which beekeepers can take.

Bees can fly up to about three miles from their colony, but most of their flying is done within one mile from the hive. A two-mile radius involves a large area, covering approximately 8,050 acres. This land may be used for a wide variety of uses including agriculture, industrial, residential, recreation, and transportation (to see the land use patterns in your location, visit Penn State’s Beescape tool). A variety of pesticides may be used on this land depending on its use. The term ‘pesticide’ includes insecticides, fungicides and herbicides.

It is important for beekeepers to understand which pesticides may be applied that can impact flying bees or the nectar, pollen, water, and propolis the bees may be collecting, and take steps to reduce exposure to these pesticides.

Beekeepers should be aware that in addition to agricultural crops, various chemicals and pesticides are used in a wide variety of places for a wide variety of reasons. Often the beekeeper will not know when these pesticides are applied.

Here are a few examples of non-agricultural locations where pesticides are often used:

- lawns for residential and business properties

- flower and vegetable gardens and other food plants

- fruit and ornamental trees

- golf courses

- parks and recreation areas

- schools and daycares

- restaurants and markets

- industries

- water and waste treatment sites

- landfills

- farm or zoo animals

- public health spraying for insects carrying diseases

- public spraying for invasive insects

- land along highways

- land along other transportation hubs

- utility right of ways along power lines or gas pipeline

Below are suggested actions a beekeeper can take to reduce their bee’s exposure to pesticides:

- Register your apiary so that it is included on the PaPlants website and with BeeCheck by FieldWatch. Pesticide applicators are encouraged to contact beekeepers near their applications to give them notice of an upcoming pesticide application.

- The PA Department of Environmental Protection has a West Nile Virus Control Program notification website. Anyone is welcome to register to receive email notification of scheduled spraying dates and general locations and the results of the mosquito testing.

Prior to the start of the growing season, talk with nearby landowners, land managers, farmers, or pesticide applicators to better understand their pesticide application program. Realize that the landowner or pesticide applicators may need to apply certain pesticides at specific times to control pests and/or diseases. Provide individuals with this document, and highlight the following key points:

- There are many pesticide options available and multiple online resources to help identify pesticides that have reduced toxicity for bees.

- Work with the landowner or pesticide applicator to have the pesticides applied at dusk or very early in the morning, when fewer bees and pollinators are foraging and the pesticide has a chance to dry or dissipate before bees come in contact with it.

- Ask the land owner or pesticide applicator not to apply the pesticide on a windy day. This reduces pesticide drift.

- Other approaches (using targeted spraying or larger droplet size) can reduce drift.

- Work with neighboring landowners and ask to be notified two day before a pesticide is applied on their property.

- Ask for the product trade name and learn the mode of action, toxicity, target and half-life of that chemical. Some products are very targeted and pose little acute risk to non-target species. Products break down at different rates, but when combined with rapid growth of early crops, most risks should be minimized in 2-10 days.

- Avoid applying synthetic miticides or apiary chemicals in hives at the same time that there is a likely exposure to neighboring pesticides. Combinations of hive controls and pesticide controls may synergize and increase toxicity to honey bees.

- Replace some old comb annually with new foundation. Toxins can accumulate in beeswax.

Beekeepers may wish to have a plan in place if pesticides are applied nearby whether the hives are moved or not. Here are some suggestions:

- Every beekeeper should have a plan for temporarily relocating hives in the event of unavoidable pesticide exposure. Hives should be moved at least one mile, preferably four miles, from the treated area.

- If moving hives is not possible, use netting or large, light colored, wet fabric to cover hives until the risk passes. DO NOT CLOSE ENTRANCES. Without ventilation to regulate inside temperatures, bees can easily suffocate. Do not cover colonies for more than two days.

- Move hives either early morning, after dark, or during rainy days. If you must move during peak flight times, leave a ‘catch’ hive where bees can gather, that can be picked up later.

- Feed bees immediately after relocating, unless they are moved into an area with good blooming floral resources. If there are not many floral resources, it may take a number of days for bees to find new floral sources.

Suggestions for beekeepers providing pollination services for crops:

- Pollination contracts are recommended. An example of such a contract can be found the Mid-Atlantic Apicultural Research & Extension Consortium.

- Develop a mutual strategy to ensure expectations and responsibilities between beekeepers and growers/owners, and pesticide applicators are fully understood.

- Exchange contact information with beekeeper, farmer, grower, property owner, and pesticide applicator.

- Determine crop treatments which are acceptable to all involved. Penn State Extension’s Pesticide Education division may be able to help with effective pesticide recommendations which are beneficial to crops and not toxic to honey bees and pollinators. Combining fungicides and insecticides in tank mixes can also be discussed. More details can be found in the “Best Practices for Pesticide Use” section of the Pennsylvania Pollinator Protection Plan.

- Define when hives will be moved in and out, how many hives will be used, and where they will be placed. Agree on the strength of the hive.

- Discuss the use and availability of access roads. Place hives to minimize problems with farm worker travel and spray routes.

- It is recommended that beekeepers consider Ag Insurance for personal liability or property damage.

- Always get the landowner’s permission to keep the bees on the property.

- The use of a ‘bee flag’, developed by Mississippi Farm Bureau, or other marker will help the grower be mindful of hive locations.

- The beekeeper’s contact information should be posted with large lettering at the apiary.

- Place hives on raised parcels of land. Avoid drop-offs, valleys or swales where chemical drift can collect.

- Beekeepers should file and maintain apiary registrations and inspection reports at their home or business.

- If necessary, construct bear fencing. Bears are in nearly every county of Pennsylvania. A map of black bear harvest can be found on the PA Game Commission’s website. These are just a few of the companies available to help with the construction of bear fences. (Listings of these commercial goods and services does not constitute an endorsement by the Pennsylvania Pollinator Protection Plan.)

Beekeepers placing colonies on natural or idle land may wish to consider the following recommendations:

- Always get landowner permission and contact information. Determine if a written contract is needed.

- The beekeeper may wish to give his or her contact information directly to the landowner.

- Develop a mutual strategy to ensure expectations and responsibilities between beekeepers and landowners are fully understood.

- Define when hives will be moved in (and out), how many hives will be used, and where they will be placed.

- It is recommended that beekeepers consider Ag Insurance for personal liability or property damage.

- Be sure access roads for field and utility workers are not blocked by hives.

- Do not locate unmarked colonies near fields or orchards belonging to another landowner or farmer.

- The use of a ‘bee flag’ marker will help the grower be mindful of hive locations.

- The beekeeper’s contact information should be posted in large lettering at the apiary.

- Maintain apiary registrations.

- Construct bear fencing. See references in the previous section.

- Place hives on raised parcels of land. Avoid drop-offs, valleys or swales where chemical drift can collect.

-

It is important to remember that a variety of factors can cause the decline or death of a honey bee colony. Pesticides are one of these factors, but many other issues may be involved. It is important to examine the bees and the hive to accurately determine the cause(s) of the problem. Beekeepers may contact the State Apiarist at (717) 346-9567 or your local State Apiary Inspector for assistance and help. Pesticide kills can also be reported to the EPA.

Different symptoms will be seen depending on the type of pesticide the bees and other pollinators are exposed to. The online booklet, “How to Reduce Bee Poisoning from Pesticides” by E. Johansen contains helpful information about symptoms, and various toxicities of pesticides for honey bees and other pollinators.

Communication is key to understanding and solving bee kills. If pesticide poisoning is suspected, bee kills should be reported to the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture (PDA). Contact the State Apiarist or the Pesticide Division through the Chief of the Division of Health and Safety as soon as possible. After talking with the beekeeper and determining if this could be a bee kill caused by a pesticide misuse, an Apiary Inspector and Pesticide Inspector will be sent to the site to collect samples and additional information as quickly as possible. Sampling of dead bees must be timely as dead bees degrade rapidly. The pesticide inspector will also be looking for signs of misuse of pesticides. Bees, and possibly some wax from the colony, will be collected, following a protocol, and taken for laboratory testing of pesticide residue. When testing is complete, PDA will file a report with the EPA. PDA Pesticide Division’s goal is to determine whether pesticide misuse has occurred, not to determine the cause of the bee kill. If proven, the person responsible for the pesticide misuse may be fined.

The beekeeper should write down as much detailed information as possible, including when the bees began dying, weather (day and night temperatures, wind, sunny, rainy, etc.), dates and types of nearby pesticide applications if known, and symptoms of dying bees. Pictures or videos of the bees are helpful.

-

Being a good neighbor is an important concern. Beekeepers have successfully kept bees across Pennsylvania from homes and business, rooftops, public and private gardens in urban areas to suburban neighborhoods to farm and rural areas for years.

Here are several management practices which will help keep the neighbors and the bees happy:

Check local ordinances to be in compliance with your municipality, a model ordinance is available through the Pennsylvania State Beekeeping Association.

Talk to your neighbors about bees.

Make sure the bees are gentle.

Place hives in a manner which directs bees to fly at least six feet air, over the heads of people and animals. Hives can be placed beside hedges, shrubs, fences, buildings, etc.

Do not place the hive with its entrance directly open to the neighbor's yard.

Provide a consistent source of fresh water near hives from early spring through late fall.

Check to be sure there are no confined animals nearby (dog kept on a chain, etc.).

Work bees on sunny, warm days when most of the foragers will be away from the hive.

Use your smoker properly.

If working bees is likely to disturb a neighbors’ outdoor activities, wait for a more convenient time to work the bees.

Read, sign and follow the Voluntary Code of Conduct For Maintaining European Honey Bee Colonies in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Give your neighbors a jar of honey!

-

Educating the public is an important, but sometimes overlooked responsibility of all beekeepers. Most people are interested and want to hear about bees. It is important to remember that many adults think there are three types of flying insects: butterflies, flies, and (if they sting) bees and, thus, are eager to learn about the different kinds of insects and pollinators in their area. Honey bees and other pollinators are very important to everyone and beekeepers are often their spokesperson.

Outreach opportunities and events can include:

- Giving a talk or demonstration at a school, children’s day camp, or scout meeting.

- Giving a talk or demonstration at a Rotary or church meeting can have a big impact on how the public views bees and other pollinators.

- Sometimes beekeepers will need to provide facts and education to local government officials at their township or borough meetings. -Think ahead and have accurate answers ready for the questions they are likely to ask.

There are many resources available for individuals interested in engaging the public. Beekeeping organizations such as the American Beekeeping Federation and other platforms including Planet Bee and The Honey Bee Health Coalition have materials, information, and/or powerpoints available for use when beekeepers give presentations. Many of the larger conferences have at least one workshop or session which provides ideas for presentations to the public. Additionally, experienced beekeepers are often pleased to share ideas and provide pointers regarding outreach when asked.

-

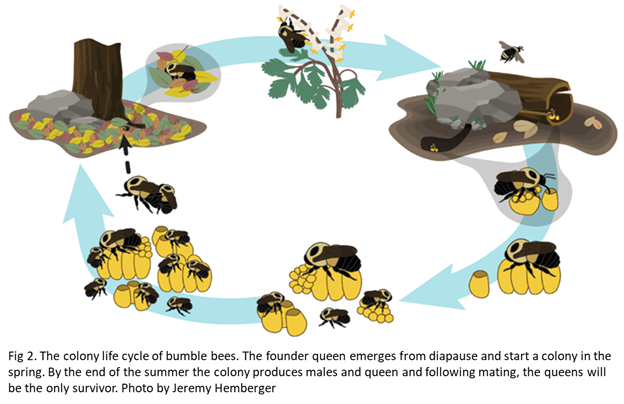

Bumble bees are social bees widely employed for pollination services worldwide. There are 260 known species of bumble bees (18 in Pennsylvania) that nest in the ground and primarily inhabit temperate areas. Unlike perennial species (such as the honey bee) that maintain a colony throughout the year, bumble bees are annual and active from spring (around April in Pennsylvania) to the end of summer (approximately September). In most species, mated queens spend the winter in diapause, a period of inactivity, underground. In spring, the queen establishes a nest - often in an underground cavity such as an abandoned rodent nest, though some species have been found to nest in bird houses - and initiates a new colony that progressively grows, reaching up to several hundred workers by the end of summer (see Figure 1 and 2). Towards the end of the life cycle, colonies produce new queens and males, with only the mated queens surviving to the next year. More information can be found in this Penn State Extension article.

Bumble bees offer pollination services to over 100 open-field crops, including cherries, berries, apples, and pears, as well as greenhouse crops like tomatoes. Unlike honey bees, they are capable of buzz-pollination, which is important for pollination of tomatoes in greenhouses. Bumble bees are active even under cool conditions, such as early in the season and early in day, when honey bees are not foraging.

While most bumble bee species are crucial pollinators in the wild, only a small number of species have been cultivated and managed. In Pennsylvania, the Common Eastern Bumble Bee, Bombus impatiens, is both commonly found in the wild and also is available to purchase from commercial vendors, such as Koppert and BioBest. More information about commercial rearing practices can be found in this Penn State article and webinar.

For people interested in trying to rear bumble bees, several helpful guides exist online, such as this and this. However, it is advised to avoid capturing wild queens of B. impatiens without expertise, considering the high similarities between species and the fact that some bumble bee species in Pennsylvania are in decline or endangered. A guide to identifying common species in the field, along with the timeline for their development, can be found here.

-

Mason bees are a solitary bee species that are used in orchard pollination worldwide, and thus many species are called “orchard bees”. Unlike the social honey bees and bumble bees, orchard bees are a solitary species and do not live in groups. Each female orchard bee will create her own nest, collect pollen for her brood, and lay her own eggs. Orchard bees are cavity nesters who typically live in cavities hollowed out by other insects or create their own nests in hollow stems and tubes. In these tubes, they will make walls from mud that they have collected (hence the name “mason bees”, and then collect pollen and nectar to form a pollen ball. They then lay an egg on this ball, and seal up the cell with more mud. You can learn more about the life cycle of the orchard bee in this Penn State Extension article, this article, or in this Penn State webinar.

Man-made structures called “bee hotels”, wooden or plastic structures with pre-made tubes, also serve as nesting habitats for orchard bees. For commercial production or agricultural management, these nesting structures can include hundreds of tubes. For the home garden, you can learn how to make and manage your own bee hotel here and here. If you create hotels for orchard bees or other solitary nesting bees, it is important to replace the nesting material so that bacterial or fungal spores do not build up and sicken your bees.

Multiple species of mason bees are used worldwide for orchard pollination. Despite 140 mason bee species being found in North America, only two species, the Japanese horn-faced bee (Osmia cornifrons) and the blue orchard bee (Osmia lignaria), are commonly managed for commercial operations. Both of these managed orchard bees are spring emerging bees, who are active for around 4-6 weeks (starting in late March to early April in PA). Male bees typically emerge first and then mate with the females that emerge afterwards. The females will then find a suitable nesting site to create their nest. Like bumble bees, orchard bees will foraging in cooler conditions than honey bees, and thus are well-suited for pollination of early spring blooming crops, such as apples.

Information on managing mason/orchard bees and others can be found in the USDA Sustainable Agricultural Research & Education program’s Managing Alternative Pollinators. Further information on mason/orchard bees can be found in orchard bees can be found SARE’s How to Manage the Blue Orchard Bee.