January 22, 2024

A Quick Lesson on the Birds and the (Mason) Bees

By Dr. Natalie Boyle

Did you know that a female mason bee can control the sex of each individual egg that she lays as she builds her nest? Mason bees pre-determine the sex of their offspring via a special reproductive strategy that scientists call ‘haplodiploidy’. One of the first things that a female mason bee does after she sheds her cocoon is mate with a male. When the bees mate, the sperm from the male travels through the reproductive tract of the female and is stored in a specialized storage organ called a ‘spermatheca’. After mating, the female will find a nest where she will collect and store an individual pollen and nectar mass for each one of her offspring.

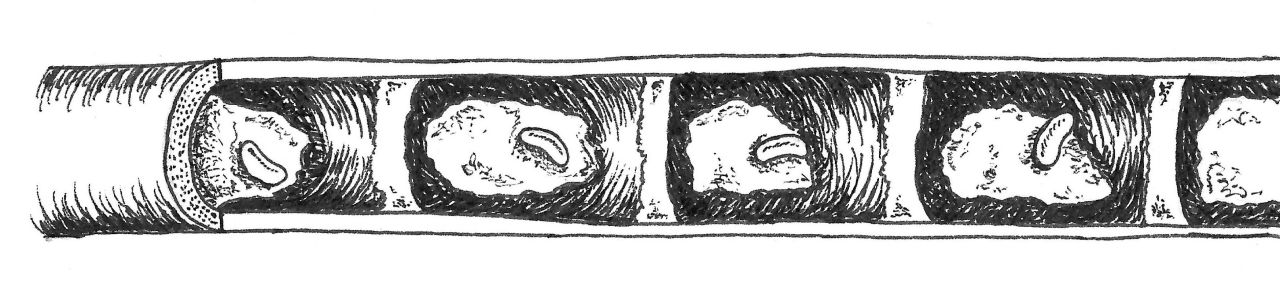

Mother bees typically lay females at the back end of their nest, followed by males towards the front end of the nest. She has precise control over the sex of her offspring due to haplodiploidy. For mason bees (and all other bees and wasps) mothers determine the sex of their offspring by deciding whether to use sperm stored in the spermatheca to fertilize the egg or not. If the egg is fertilized, the egg is destined to become a diploid female. The egg and sperm combine to yield two sets of paired chromosomes in the offspring, just like all of us humans have. If the egg does not get fertilized by sperm stored in the spermatheca, the egg is destined to become a haploid male. Without any sperm fertilizing the egg, there is no second set of chromosomes for the developing bee to inherit. This means that all male bees and wasps contain half the amount of genetic information that female bees and wasps do!

So, as a mother mason bee establishes her nest, the first eggs that she lays are fertilized using the sperm stored in her spermatheca so that they will develop into females. After she constructs a few female cells, she will transition to producing male offspring – and these are the eggs that will be left unfertilized, so that they will develop into males.

Studying reproductive fitness in mason bee males

If female mason bees do not mate or are poorly mated in the spring, what happens? Well, then they may not be able to lay any diploid female eggs in their nest, and more males are produced. Without female mason bees, the quality of pollination that mason bees provide, and their resilience across generations becomes threatened. For this reason, researchers at Penn State University are currently exploring the role of environmental stressors on the quantity and quality of mason bee sperm. Mason bees are subject to many different stresses throughout their life, which can include pesticide exposure, unpredictable shifts in local weather conditions, or limited access to healthy/diverse pollen and nectar resources.

Previous studies have demonstrated that male bumble bees and male honey bee sperm can be compromised after exposure to heat stress or chemical exposure. Similarly, when honey bee males are fed a sugar diet with pesticide mixed into it, we see adverse impacts on the quality of their sperm. To date, there is only limited data available on the role of stress on male mason bee sperm, and no baseline data on the innate viability and abundance of western mason bee species such as the blue orchard bee (BOB) and Japanese orchard bee (JOB).

During Spring 2023, Drs. Natalie Boyle and Jaya Mokkapati of Penn State partnered with Dr. Lars Straub and his master’s student, Johanna Hehl of the University Bern in Switzerland to investigate sperm quality in western mason bee species. Together, they collected male mason bees of different ages to examine the rate at which the sperm matures over time. This protocol includes the dissection of the male testes, from which the sperm are treated with two different fluorescent chemical stains (one binds to live sperm and the other to dead or immature sperm). From fluorescent microscope images, they are able to estimate amount of sperm and proportion of viable (living) sperm recovered from individual males.

This spring, additional trials are underway to explore the effect of heat stress on the sperm quality of males by introducing managed JOB populations to different thermal treatments prior to measuring sperm abundance and viability. This will help us to understand the potential role of climate change in contributing to bee population declines, and to determine whether different mason bee species might respond differently to similar outward stressors.

If you have any questions about this research or want to learn more about pollinators in general, you can email Natalie Boyle and/or visit Penn State’s Center for Pollinator Research website.